When designing their nation-wide electronic traceability program for seafood, the Philippines decided to start from scratch. With a valuable tuna fishery at stake, and a convergence of people, events, and regulations, the Philippines’ journey of self-reliance inspired a monumental collaboration. Developing a unique method to seamlessly exchange information along this seafood supply chain was not without pitfalls. Digitizing an archaic system of paper records to improve seafood tracking had been carried out in other countries. But how this country overcame its hurdles can serve as a model for others. The Philippines’ electronic traceability program has already been used to track and verify the legality of over $20 million USD worth of tuna export. Here is their journey.

This resource was created to be particularly useful for government staff that would like to learn best practices for implementing electronic seafood traceability systems. It is also useful for NGOs and industry groups that work alongside them.

But first - why did the Philippines create an electronic traceability program?

But the waters surrounding the Philippines that make up this ‘tuna highway’ are vulnerable to illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. IUU fishing damages fish stocks around the globe, costing the global economy anywhere from $26 to 50 billion dollars (3), and can even occur alongside human rights abuses at sea.

IUU fishing may cost the Philippines over USD $620 million per year (4).

In 2014, the Philippines received a formal warning from the European Union for inadequately addressing IUU fishing, which warned that continued inaction might lead to a ban on seafood from the Philippines entering the EU market.

The Philippines’ government had to address IUU fishing to protect market access and sustain the health of the biodiverse ocean surrounding the Philippines.

So they moved towards electronic traceability, which can both mitigate IUU fishing by increasing the transparency of supply chains and improve stock assessments and fisheries management by capturing more data.

Bringing everyone together

The Bureau of Fisheries and Aquaculture Resources (BFAR), the division of the Philippines government responsible for the management and conservation of fisheries, passed a policy to strengthen the country’s stance against IUU fishing and implement a more rigorous traceability program.

The government didn’t create this updated traceability program on its own, however. Indeed, they had quite a bit of help from both NGOs and the private sector.

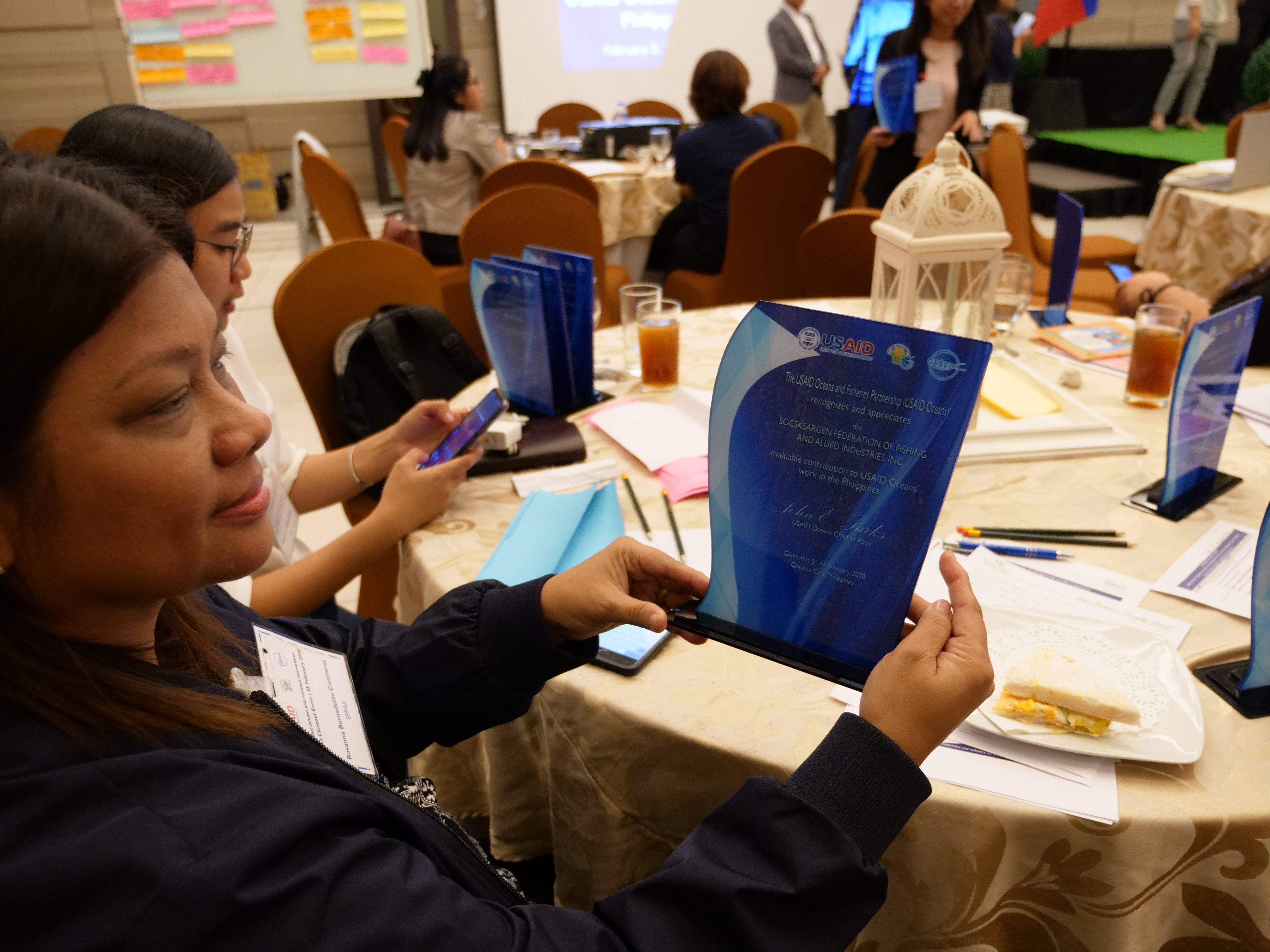

The USAID Oceans and Fisheries Partnership (USAID Oceans) worked to help BFAR expedite the transition from paper to electronic traceability. They also brought in private industry, fishers, and NGOs to get their feedback and ensure this program would work for everyone. One USAID Oceans grantee was the SOCSKSARGEN Federation of Fishing and Allied Industries, Inc. (SFFAII). SFFAII is a non-profit organization that represents over 100 seafood-related companies, from capture to processing, and even two aquaculture companies. With the help of SFFAII, 13 different companies from the seafood industry participated in the design, testing, and implementation of the electronic traceability program.

They all understood that building ownership into the project is integral to committing long-term to use it.

Ultimately, the government will allow data from the processors’ internal systems to feed directly to BFAR’s programs, to reduce redundant data entry. The lack of internal tracking alignment will likely be a point of consideration for other governments and showcases the ability of the Philippines government to co-create a program with the seafood industry that works for both parties.

Although the government certainly had a solid foundation to work from due to the industry-inclusive policy, more lessons arose during the consultative process:

- Even with consultations, engaging more with local government officials and private industry may have been beneficial. For instance, the original traceability policy had to be amended as it focused on purse seining and canning and not on handline/fresh tuna supply chains. To incorporate that aspect of supply chains, they had to adjust the data they were collecting.

- Distant water fleets are still not covered in the amendment, so the government acknowledged multiple iterations of the policy will likely occur as they modify for the data collection needs of other supply chains.

Creating the technology architecture

Before BFAR could create the traceability program, they had to answer the question: how should the data be collected? So they held multiple rounds of workshops to identify the critical pieces of data and how best to capture them.

Fishers and processors had been manually collecting the data required for export to some countries (e.g., European Union and the U.S.). With an electronic traceability program, they could now collect and share additional data, and also improve the quality and accuracy of the data.

Once all of the stakeholders understood how best to collect their essential data, they could create the traceability program.

Fortunately, governments now crafting their own traceability programs don’t have to start completely from scratch to determine what information they should capture and how; in 2020, the Global Dialogue on Seafood Traceability created a standardized list of recommended data to collect.

Their lead developer never expected to be holed away for five days a week at a ‘Development Camp’, but that’s where he found himself for three months straight, working alongside 10 other developers to create a traceability prototype.

Fortunately, the developers had a solid foundation to start from. They could create their technology architecture based on the manual, paper-based record-keeping system already in place.

The developers learned many valuable lessons while constructing the traceability program, such as:

- Without dedicated servers supported by robust network infrastructure, the program–which involved many software applications–worked too slowly

- The biggest challenges were not on the back-end or technical side of things, but on the front-end where the user interfaced with the software

- Though developers do not necessarily have a fisheries background, it was essential they understood the supply chain process to produce an effective product

- Close coordination and communication with users were important to ensure the program worked effectively. Developers were occasionally sent directly to the field to address bugs and fixes identified by users

After they developed the program, capacity building and troubleshooting began. USAID Oceans provided technical support and training to industry stakeholders as they tested the technology and gave feedback to the developers to produce the best program they could.

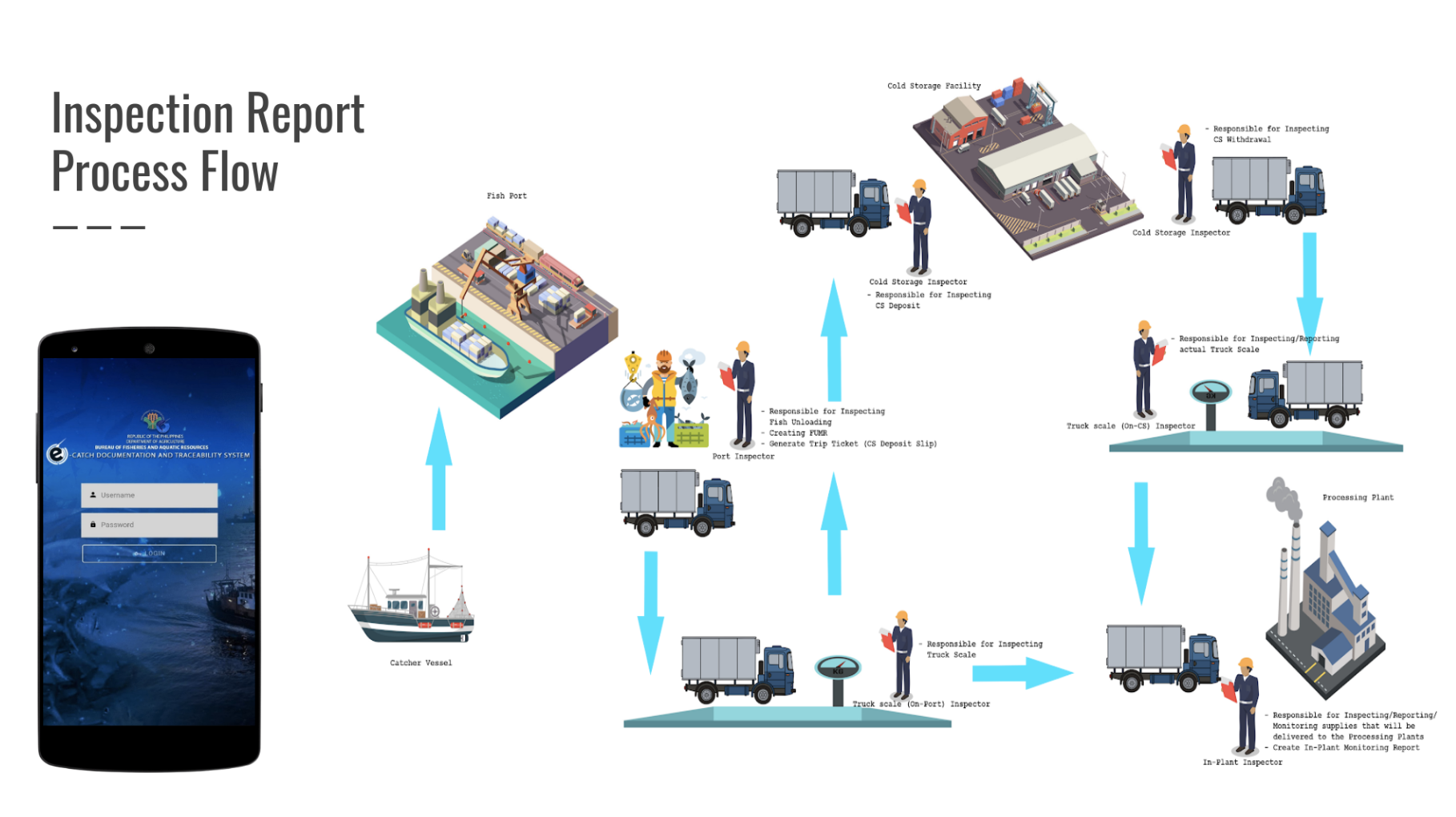

The program

The program itself works similarly to a mass balance, where the volume of catch at the point of entry should align with the same volume at multiple checkpoints throughout the supply chain.

For more in-depth information on the electronic traceability program, its architecture, and the process behind its creation, visit this resource.

Launching the pilot

Once the electronic traceability program was created, a pilot location was selected: General Santos City on the southernmost island of the Philippines.

Rosanna Contreras is the Executive Director of SFFAII, and possesses substantial insight into the industry perspective on creating this traceability program.

According to Rosanna, there are two principal factors that encouraged the private sector to participate in the pilot and development of the traceability program:

- First, there is potential for electronic traceability to add value to their products.

- Second, they have considerable incentive to contribute input to the design.

By participating in the pilot, industry stakeholders could express their opinions on the regulatory frameworks to help reduce the number of amendments needed and create policies that benefit both government and business. In addition, they could advocate for communications that would work for them (e.g., imagery integrated into the software for illiterate fishers), and troubleshoot through Facebook groups and regular focus group discussions held with the support of USAID Oceans.

As mentioned earlier, governments can’t do it alone. In addition to the hours of USAID sponsored workshops and training, industry put in many hours to pilot this traceability program too.

According to Rosanna Contreras, SFFAII contributed approximately 4.8 million Philippine pesos in terms of staff hours.

Incorporating small-scale fishers into the program via electronic catch documentation

To have electronic data throughout every step of the supply chain, it has to start on the water with the fishers. But, as one artisanal fisher put it, they are “there to fish, not to document.”

To capture information electronically and easily at the fisher level, BFAR partnered with a technology vendor: Futuristic Aviation and Maritime Enterprises (FAME).

Fishers can’t record data on a smartphone at sea. FAME helps to get around that issue by using vessel monitoring systems on boats that use radio frequencies to ping gateways on land to monitor location and time of catch, allowing fishing activities to be tracked and monitored.

However, some challenges persist with expanding this electronic catch documentation pilot, namely that implementing electronic traceability can put a considerable cost onto small-scale fishers. As a result, many are resistant, and the primary reason some agreed to take part in the pilot was that the program covered the costs in the short term.

Benefits

Electronic catch documentation and traceability programs cannot only improve fisheries management and serve as a tool to mitigate IUU fishing risk, but they can also lend direct benefits to governments, businesses, and even fishers who implement these programs.

Government

Before the electronic traceability program was put into place for the Philippines, fisheries reports and stock assessments were viewed quarterly. But now, since the information is electronic, fisheries managers have greater access to data and can use this to inform day-to-day decisions.

Previously, stock assessments contained data on the quantity of catch at landing. Now, managers have access to additional information, such as the location of catch.

Businesses

Some businesses that took part in the pilot reported more efficient record-keeping, more timely data, faster generation of required documents and certificates, and greater transparency overall, according to a panelist at USAID Oceans’ closing event.

From the trade association, Rosanna Contreras stated that electronic traceability can build more efficient operations, qualify businesses for certifications that are increasingly being requested of their products, and recall products quicker to create a safer seafood industry overall.

Small-Scale Fishers

One innovative businessman is using the small-scale fisheries pilot technology to move closer to obtaining a sustainability certification. As a result, he pays fishers a premium if they use this pilot technology to track where and when they’ve caught their fish—one example of a potential financial benefit for small-scale fishers from this technology. The hope is that others will adopt similar business practices once they realize the value of more transparent seafood products.

This traceability technology also allows fishers to stay in contact with relatives onshore if they decide to take phones with them. The traceability platform has messaging capabilities, so fishers can contact their loved ones to let them know they are safe. In one instance, this traceability technology helped to alert officials that a fisher’s boat had nearly sunk since his tracking device kept pinging in the same spot.

Although increased safety, connectivity with loved ones, and financial incentive are all potential benefits of traceability programs, more could be done to ensure that small-scale fishers reap the full benefits of using electronic traceability.

Looking to the future—what's next?

The pilot project in General Santos City has wound down, but some see it as just the beginning.

The end of the pilot marks the start of rolling out the electronic traceability program nationally. It marks a transition to local government ownership of this initiative as they incorporate other commodities, like the blue swimming crab, into the program. BFAR also continues to research and test how to implement electronic traceability in municipal fisheries.

The Philippines made incredible progress in creating a national electronic traceability program while weaving in gender equity, social responsibility, and transparency. However, multiple government officials, technology developers, and private industry stakeholders attested that it would have been beneficial to hear more about the traceability programs of others before creating their very own. As an initiative designed to share knowledge about traceability, the Seafood Alliance for Legality and Traceability (SALT) understands that plea. Helping pilot projects learn from one another to collectively move the field of traceability forward is SALT’s mission. We hope this story can serve as a model and inspire others to follow suit.

Seafood Alliance for Legality and Traceability (SALT) is a public-private partnership between USAID and the Walton Family, Packard, and Moore Foundations, and implemented by FishWise, a sustainable seafood consultancy. SALT is a global community of governments, industry, and non-governmental organizations working together to share ideas and collaborate on solutions for traceable and sustainable seafood. To learn from other traceability pilots and case studies from around the globe, visit SALT’s traceability resource repository. If you have a case study you’d like to share, please let us know.

Thank you to USAID Oceans for hosting SALT at the closing event in the Philippines, and for all of the BFAR representatives and USAID Grantees that gave their time to be interviewed. A special thank you to Becky Andong for her guidance, warm welcome, and expertise. If you’d like to read more about the breadth of lessons learned during the design and piloting of this electronic traceability program, read the full report here.

References:

3: Illicit trade in marine fish catch and its effects on ecosystems and people worldwide