Paving over the Global Gender Gap in Fisheries- Dispatch from the Philippines

Bringing women into the fold

The Philippines

Mildred Mercene-Buazon doesn’t mince words when clarifying that gender equity is not about just counting the numbers of women and men present in a room. One first needs to start with appreciating the minority sex. “Appreciation is the biggest gap in gender work,” says Mercene-Buazon. The roles and contributions of women in fisheries were not fully appreciated, she says, particularly by policymakers. Though they contribute significantly in activities beyond harvesting, “they are being counted always in the hemline.”

As the Chief Administrative Officer and Vice-Chair of the Gender Focal Point System for the Philippines Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) Central Office, Mercene-Buazon channels further inspiration from another gender specialist: Arlene “Jigsz” Nietes Satapornvanit. They both worked on the USAID Oceans and Fisheries Partnership, an initiative combatting illegal fishing in Southeast Asia that also supported an electronic traceability system for the Filipino tuna fishery. They worked to address human welfare and gender for the program. One simple method to foster gender awareness? Feature a woman in their supply chain graphics, says Jigsz (which they did).

SALT visited the Philippines in January and February 2020 to gain detailed insight and interview those working on the Philippines’ traceability endeavor with USAID Oceans. While browsing banners in a Manila hotel event room celebrating the program’s close, it appeared women were the majority in Southeast Asia’s fisheries. Upon closer inspection, it was actually a showcase of gender champions who supported equity and empowerment for women in the seafood industry, because female contributions in fisheries have been largely ignored.

With fishing roles in many cultures traditionally reserved for males, more recent concentration on gender equality shows where and how we’ve overlooked women in this field (more stories below). After all, women, too, depend on marine resources for survival, feeding their family, and account for nearly half the fisheries workforce. Without sex-disaggregated data though, it’s challenging to address gender in programs. The often-cited resource from 2012 on women’s contribution to fisheries showing that women are 50% of the workforce illustrates the dearth of gender-specific data. Sex-disaggregated data is missing from more recent reports like FAO’s 2018 State of Fisheries and Aquaculture report, which compiles data from many countries. Not only is the data not collected uniformly through a gender lens, but those numbers also exclude other sectors, like processing or marketing. “How do you measure the impact of women in fisheries if there is no data?” asks Jigsz.

Show me the data

Thus, USAID Oceans began with a gender analysis in General Santos, the tuna capital of the Philippines, assisted by the National Network on Women in Fisheries in the Philippines, Inc. (WINFISH) with Dr. Marieta Sumagaysay as Project Leader. Carrying out the analysis itself imparted awareness, says Sumagaysay, even with the data collectors themselves who came from Mindanao State University but were not in a gender field. It also helped differentiate where women and men differed in their needs by asking each gender what they perceived other genders needed. Other issues also emerged from the gender analysis. WINFISH, through a grant from USAID Oceans, implemented gender interventions to address them.

One interesting finding was that more males than females thought women had not been encouraged to join fishing trips. That could be attributed to less support from friends and family based on beliefs about women’s household role, or the purported level of stamina required for fishing. Furthermore, persistent cultural beliefs that women can cast bad luck on fishing might keep them from boarding boats. However, very few women actually expressed a desire to go to sea. Recommendations broke out what could be done practically to meet women’s needs (e.g. designated nursing areas), versus strategies to break up cultural norms (e.g. designing women-friendly boat facilities, give forklift driving lessons) (column below).

At the time of SALT’s visit, they had not yet put many findings to the task. Sumagaysay points out a need to boost the capacity for people to monitor gender programs. Awareness was one thing, but without oversight, how does an organization know it checked the boxes? It’s not enough to be sensitive to gender needs; it’s about responding to those needs.

As the analysis notes, the Philippines has consistently been the only Asian country with such a low gender gap in fisheries. In fact, the Philippines government mandates that five percent of its annual budget for each agency be allocated to programs for gender development. Those plans are subject to auditing and must be endorsed by the Philippine Commission on Women. One doesn’t have to wonder how to start weaving gender into programs; guidelines exist!

Reeling in fisheries

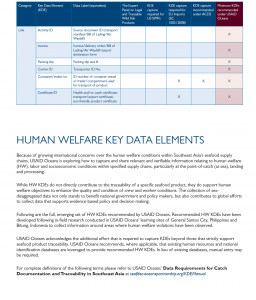

Gender and Development checklists help BFAR assess whether it adequately incorporated gender into its fisheries programs. BFAR already stood out within the Department of Agriculture as leading on gender sensitivity, said Mercene-Buazon, but the analysis really encouraged those determining fisheries policy to jump on board. The USAID intervention also ratcheted awareness up for policy makers by spelling out specific activities, and showing they could bring gender into their electronic traceability pilot, says Rebecca Andong, Country Coordinator for USAID Oceans. In addition, the project developed a gender training handbook in collaboration with other experts for sustainable fisheries management. Based on research in the Philippines and Indonesia, USAID Oceans also put together a list of data to collect in fisheries that relate to human welfare and gender (pg 10-11).

into its fisheries programs. BFAR already stood out within the Department of Agriculture as leading on gender sensitivity, said Mercene-Buazon, but the analysis really encouraged those determining fisheries policy to jump on board. The USAID intervention also ratcheted awareness up for policy makers by spelling out specific activities, and showing they could bring gender into their electronic traceability pilot, says Rebecca Andong, Country Coordinator for USAID Oceans. In addition, the project developed a gender training handbook in collaboration with other experts for sustainable fisheries management. Based on research in the Philippines and Indonesia, USAID Oceans also put together a list of data to collect in fisheries that relate to human welfare and gender (pg 10-11).

While WINFISH’s Sumagaysay points out not all the groups working with BFAR had reached the same level of awareness, she gave a breakdown on how gender could be woven into electronic traceability work that goes beyond the Philippines:

- Involve more women from the beginning, even during monitoring and recording the data. It’s not about inviting equal numbers of men & women; make sure they’re all equally engaged. Ensure the facilitator holding any workshops is sensitive to gender needs.

- Conduct a gender analysis. Look at the difference between men’s and women’s situations in supply chains (e.g., roles, responsibilities, opportunities, access to resources). Use different analysis techniques to ensure issues are not perceived by one gender, but that they are actual issues.

- Define gender-sensitive indicators.

- Allocate a portion of the budget to gender research. Even if a budget exists, develop training on how to carry out gender research. Include gender in the organization’s goals when possible (e.g. “empowering both men and women”).

- Ensure that the recommended solutions to address gender don’t lead to another gender problem.

Casting wider

What does it look like if a company has already woven gender equality into its policy? Well, it seems a gender expert might still be necessary because carrying ideas out and monitoring progress requires oversight. To sustain a gender movement within an organization and call it successful, Sumagaysay listed a few more essentials: people and time. Additionally, gender champions need to be on hand, and management especially needs to buy in. The gender staff role should be the sole role for that person. Finally, beyond strong collaborations, it is helpful if the company has the ability to influence national agencies.

In recalling Mercene-Buazon’s words that gender is not about numbers of men versus women, I hesitate highlighting that our trip to the Philippines involved interviewing 17 people, 9 of which were women. Furthermore, we only questioned women about gender issues. Thus, one of SALT’s lessons from the trip is that we may have gained more gender insight posing gender questions to the men. In essence, the knowledge and tips we gathered were illustrative of SALT’s raison d’être: learning from each other helps advance progress in a field.

So why share what one country has done? “We are inspired by sharing experiences and practices of neighboring countries,” says Mercene-Buazon.

SALT couldn’t agree more.

Thus, in the spirit of knowledge exchange, we ask our readers to share with us and others how they integrated gender into their projects. Particularly when gender disparities in seafood may grow during the COVID-19 pandemic, swapping lessons is more important than ever.