I have worked in the seafood industry since 2011 and have been studying and assessing seafood products for environmental sustainability since 2013. I now work for FishWise, a non-profit sustainable seafood consultancy that provides guidance and resources for companies to develop and implement comprehensive sustainable seafood programs. At FishWise, I am on the business engagement team, where I help assess and recommend sustainable seafood products to some of the largest retailers in North America.

A common question I hear from friends and family is: how do I buy sustainable seafood? In the past, I have responded with a few practical considerations for the grocery store, or tips for buying locally landed species when in season. But recently, that question has come with an added skepticism, in part due to a recent Netflix film, Seaspiracy, that controversially concluded, “there is no such thing as sustainable seafood.”

This claim is empirically untrue and was comprehensively refuted by almost every expert in the sustainable seafood space following the film’s release. But viewers of the film are now more confused than ever about which seafoods are best when considering sustainability, both environmentally and socially.

As a leading seafood sustainability consultant in North America, FishWise is uniquely suited to answer this question. Our message is quite the opposite: there are many sustainable seafood products available, regardless of where you live or do your shopping. If you understand a few basic considerations, and check your favorite grocery store chain’s seafood sourcing policies, you’ll be able to confidently choose environmentally sustainable seafood products anywhere in the country.

A Foreword on Holistic Sustainability

My professional expertise is in the environmental sustainability of seafood, and that is my primary focus of the following recommendations. However, FishWise defines sustainability holistically, which includes many more considerations than solely the direct environmental impacts of harvesting wild and farmed seafood species. Social responsibility is a core component of this holistic sustainability definition, and human and labor rights abuses in seafood supply chains were indeed part of the film Seaspiracy.

However, rather than provide potentially incomplete advice for purchasing socially responsible seafood, I want to alert you of this omission before you read further and defer to my colleagues and the resources on The Roadmap for Improving Seafood Ethics (RISE) for guidance on socially responsible seafood considerations.

My environmental sustainability recommendations often overlap with social responsibility recommendations, but not always. I will do my best to point out these gaps.

Choose Seafood Products from the USA (whenever possible)

The first piece of advice I typically offer is to choose seafood with “USA” as the country of origin. Generally, if it’s caught or farmed in the U.S., you can have a much higher level of confidence that the product is environmentally sustainable.

The U.S. has robust fishery management laws that are designed to rebuild commercially harvested species, or “stocks”, and prohibit and penalize overfishing. The use of “best available science” and “maximum sustainable yield (MSY)” is literally written into the Magnuson-Stevens Act, the legislation providing for the management of marine fisheries in U.S. waters. Couple the Magnuson-Stevens Act with the Endangered Species Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the National Aquaculture Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and NOAA Fisheries’ commitment to ecosystem-based management, and you have a system completely devoted to maintaining and rebuilding fish stocks. The current legal framework in the U.S. requires fisheries to be rebuilt, as quickly as possible, to levels that will produce a maximum sustainable yield, even if that means foregoing a slightly slower, but far more lucrative rebuilding trajectory. It is illegal to harvest seafood unsustainably in the U.S. Thus, if you are able to determine that the U.S. is the country of origin for a seafood product, then you can generally rest assured that these environmental sustainability principles apply to that item.

You might have noticed that many of the fisheries management benefits I described above are more directly applicable to wild fisheries than aquaculture operations. A common misconception among consumers is that aquaculture cannot be sustainable, which is absolutely untrue. For example, many of the farmed seafood industries based in the U.S. have very strong environmental sustainability reputations (oysters, mussels, clams, and catfish are examples that come to mind).

Country of origin labeling is a U.S. law that requires food retailers to notify customers of the origins of meat, seafood, and produce. The law was established in 2002, expanded in 2008, and provides an essential data element for determining sustainability.

Unfortunately, the COOL law has a few blind spots. In 2008, the law was modified to allow certain commodities that are further processed outside the U.S. to retain their U.S. origin on the final package. A common example is Alaskan wild salmon, caught in the U.S., frozen and sent abroad to be processed at lower labor costs, then re-shipped to the U.S. and sold with “Product of U.S.” on the label. The robust fishery management laws in Alaska still apply, but shipping the fish abroad to be filleted raises questions of carbon footprint, social responsibility, and traceability, since we now must rely on the systems of other countries, many of which have less comprehensive oversight capabilities. A piece of salmon caught, landed, processed, and sold in California would carry the same COOL as a piece of Alaskan salmon sent to another continent for processing, and then back again in this manner.

Another caveat: the U.S. COOL product does not guarantee human and labor rights were upheld throughout the supply chain, even if it stays within the U.S. border throughout production. In recent years, human rights abuses have been reported in Hawaiin fishing fleets, and processing facilities in New England, the Gulf coast, and Alaska. Few countries and even fewer industries are exempt from human and labor rights challenges. While the U.S. offers better supply chain oversight than most, it would be inaccurate to state that all U.S. seafood products are socially responsible.

It’s worth noting that the two most popular seafood species for U.S. consumers are farmed Atlantic salmon and shrimp, both of which are mostly imported. So, while it might seem straightforward to look for the U.S. COOL label when purchasing seafood, you should be prepared to encounter many imported offerings. In fact, the U.S. imports the majority of the seafood it consumes, with a recent estimate being between 62-65%. A seafood buying guide must speak to this two-thirds coming from overseas, especially considering there are many other countries practicing comprehensive fishery management strategies that deserve consumer appreciation. Melnychuk et al. found a correlation between healthy fisheries and sound management. The U.S., Iceland, Norway, and New Zealand featured some of the healthiest fisheries when measuring research, management, enforcement, socioeconomic, and stock status. By these measurements, well-managed fisheries exist all over the world and will be represented at your grocery store.

Understand the Role of Ratings and Certifications

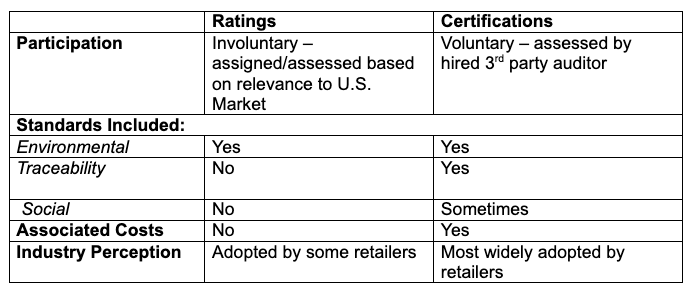

Informed environmental sustainable seafood purchases require more than just COOL when dealing with products that cross international borders. Before delving into complex environmental considerations like catch methods, fish stock abundance, and regional fishery management schemes, as they relate to that piece of swordfish or that bag of shrimp you’re considering for dinner tonight, it’s worth first considering seafood ratings and certifications. These tools are the backbone of many credible seafood sourcing policies. They are the benchmark, the global standard for environmental sustainability, and based on peer-reviewed, best available science.

If seafood sustainability ratings and certifications are the be-all-end-all, then why didn’t I start my guide with this suggestion? Because they’re tricky to understand and use correctly, and they may require information not available at the seafood counter or on the packaging of a seafood product. However, when you are able to get the information you need, these tools can provide you with the clearest possible understanding of a seafood product’s environmental sustainability.

The most common environmental rating in the U.S. is the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch Program (SFW). It rates seafood sources from all over the world, both wild and farmed, but emphasizes those most relevant to the U.S. market. This means some near-shore fisheries, bycatch species, or international fisheries might not be rated—which doesn’t necessarily mean that they are unsustainable- they just fell outside the bandwidth of the SFW assessment team. SFW updates each rating every few years, with priority given to those atop the U.S. market. This is a massive undertaking and one which deserves more acclaim and support.

Environmental sustainability ratings for seafood generally measure three primary considerations:

- Fish stock abundance

- Ecosystem impacts of harvest and/or production

- Fishery management effectiveness and regulation

This is a major oversimplification of seafood environmental sustainability ratings and certifications, but if the fish is abundant, the harvest of that fish has minimal impact on the surrounding marine environment (and in the case of farmed seafood, the inputs to rear that seafood have a low environmental impact), and there is robust management in place to hold harvesters and producers accountable, then that source will be rated favorably for environmental sustainability.

SFW has communicated its ratings in a variety of ways over the years. Initially, the program created wallet cards that could be found on the tables at some seafood restaurants or at the fish counter at grocery stores. They also had a mobile app for quick access to ratings. Now SFW ratings are solely presented on a recently overhauled website to be more consumer-friendly.

But finding the correct rating can still be overwhelming to the uninitiated. You must know the fishing method, catch region, and both the FDA common name and the scientific name to properly navigate all SFW ratings. This can be tricky even for trained professionals, let alone the average shopper. Unfortunately, SFW can’t be flexible on these key data elements without losing some of its consistency and credibility, so you’ll just have to work with it the best you can.

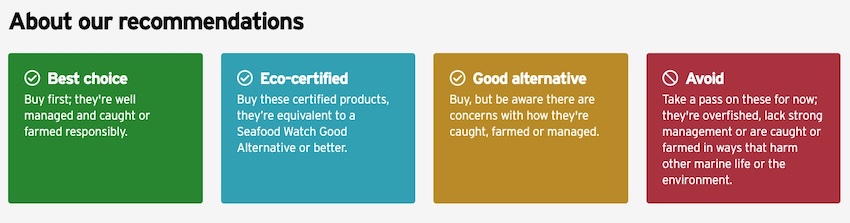

SFW ratings follow the traffic light system:

Most companies that rely on SFW ratings consider green or yellow-rated seafood as “sustainable.” SFW uses a precautionary approach to its ratings, so if a product ranks as green or yellow, you can feel confident buying it for environmental reasons. To read more about the exact methodology of the SFW rating system, visit here.

It is important to note that SFW does not currently consider social responsibility indicators in its seafood ratings. The organization includes social responsibility into its definition of “sustainable seafood” and helped develop the Seafood Slavery Risk Tool, but they defer to other organizations on this subject.

SFW works closely with wild fishery and aquaculture certification schemes to avoid duplicative efforts. A common example is that SFW has retired all of its Alaskan wild salmon ratings. Of course, wild salmon caught in Alaska is highly sustainable and very relevant to the U.S. market. However, much of it is also Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certified. So rather than duplicate the existing certification, SFW has “eco-deferred” its environmental sustainability ratings for all Alaskan salmon fisheries to eco-certifications.

There have been practical efforts to streamline how certifications and ratings co-exist, including Seafood Watch’s use of the eco-deferral system. However, there are inevitably situations that can be confusing for consumers to navigate. For example, customers that rely on SFW ratings might wonder why a highly sustainable product like Alaskan salmon appears unrated, when it is technically MSC certified. There is also another gap whereby smaller domestic producers might not have a rating or a certification, barring them from selling to companies with stricter sustainability requirements. If you generally favor U.S. seafood like I suggested, the confusion amongst environmental sustainability schemes shouldn’t be as much of an issue.

SFW most commonly eco-defers to these three certifications:

The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) – the largest seafood certification body in the world; currently assesses about 17% of global wild fish production. The MSC has not historically incorporated social responsibility considerations into its certifications, but they are beginning to expand the scope to address forced and child labor issues.

Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) – the aquaculture equivalent to MSC certification. Like MSC, ASC has robust traceability standards. ASC does include a social standard aimed at prohibiting child labor and forced labor, ensuring the health and safety of workers, and expanding workers’ rights.

Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) – the most widespread certification for farmed seafood. BAP also has standards that address, “social accountability,” in farmed seafood.

MSC and ASC are a pass/fail system—a product is either certified or not.

BAP, on the other hand, uses a 4-star system. Each star applies to one element of input for the product being certified: farm, processor, feed-mill, and hatchery. If a product has a 4-star rating on the package, it means all of these facilities were assessed for environmental and (some) social sustainability considerations. The most common ratings you’ll see are 2-star (farm and processor) and 4-star.

One last important note: everything involved in these ratings and certifications is publicly available. The MSC has a diversity of private, public, and non-profit voices on its advisory boards, they publish reports on the progress of their certified fishery partners, and every pending certification is open to comment and critique from environmental groups. SFW invites industry to ratings update calls each month and publishes public reports on every ratings change. Consumers can even sign up for email alerts to make sure they are always updated.

Believe it or not, there is a ton more I could say about seafood sustainability ratings and certifications. But your head is probably already spinning with all this information. Ratings and certifications are complicated, even for trained professionals. Certifications at the point of sale in the U.S. are also not as widely adopted as they are in other countries, so it can be difficult to rely on them at U.S. grocery stores.

Rely on Your Local Grocery Store’s Seafood Sourcing Policy.

The majority of the largest grocery stores in the U.S. have publicly available seafood sourcing policies, easily findable on their websites. There are varying degrees of rigor and depth to such policies, but I suggest you begin with your local go-to grocery store and see what you can find. Ideally, the policies would encompass environmental, social responsibility, and traceability components. The Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions produced a Common Vision to guide seafood businesses on building sustainable seafood programs, and its recommendations are consistent with best practices for U.S. grocery store chains.

When evaluating a seafood sourcing policy, look for answers to these questions:

- Which products does this policy actually cover?

- The first step should be to look at the scope of the company’s seafood sourcing policy. Does it cover all seafood products, or just private label brands? Sometimes a grocery store chain will only apply a sourcing policy or a sourcing goal to a discrete set of seafood products, while still offering other seafood products outside those specifications.

- How does this company define “environmental sustainability?”

- The more specific language you find, the better. For environmental sustainability, most grocery store companies rely on certifications like MSC, ASC, and BAP, but some have expanded their definition to include SFW and other rating systems. If a retailer’s website just says “our seafood is sustainable” without providing additional details, you have good reason to be skeptical. If you’re still unclear after some online research, ask by email, on social media, or in the store on how they define environmental sustainability.

- An important caveat is that some smaller retailers may not have the capacity to invest in a specific sourcing policy, or at least not one that is published on their website. This doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t source to specific sustainability standards. When in doubt, ask them about their standards and you might be reassured. This also signals to them that you, the customer, cares about these details being described publicly, which is always a positive message to send to this industry.

- How are companies verifying sustainability claims?

- Some grocery store chains self-regulate and self-report on sourcing standards and progress (small retailers usually must do this themselves for practical limitations), but having an independent, third-party partner (like FishWise), and a reliable electronic traceability platform, adds credibility to a retailers sourcing program. If such partnerships exist, they will be described somewhere on the grocery store’s website. Look for third-party partnerships like this whenever possible.

- Is the company making progress or is it static in its sourcing goals?

- Another way a company can demonstrate it is serious about sustainability is by making an explicit time-bound commitment. “By year X we will source X% of X”. In reality, there have been plenty of corporate milestones quietly missed that consumers don’t remember. In the eyes of shareholders and upper management, these milestones are never overlooked, but true accountability varies. Even so, a time-bound and specific seafood sourcing goal is definitely a good thing that adds an extra step not all companies are willing to take, and provides important transparency and practicality to a sourcing strategy.

- Do they address social responsibility?

- Social responsibility issues in seafood are often linked with environmental concerns because both persist in opaque supply chains where management and accountability are absent. But social responsibility is a distinct field deserving its own considerations and planning. The seafood ratings and certifications I described above were originally created to provide environmental assurances and therefore do not fully account for responsible recruitment, decent work at sea, and worker engagement, if they incorporate social responsibility at all. Because social responsibility is confusing not only for consumers but for companies to navigate, FishWise developed the Roadmap for Improving Seafood Ethics (RISE) to consolidate guidance and provide businesses with streamlined human rights resources to meet their specific needs. Choose grocery store chains that incorporate RISE guidance.

- Many large U.S. retailers may already have some social responsibility considerations for their supply chains related to other product categories. However, there are some uniquely difficult challenges in seafood supply chains that require special consideration (transshipment and distant water fleets for example), and if a brand is making specific efforts to assess its seafood supply chains for these vulnerabilities, they deserve your patronage.

Here are the top 5 grocery store chains in the U.S. (by revenue, 2020) and their publicly available seafood sourcing policies:

I want to reiterate that these recommendations for evaluating a seafood sourcing policy may favor the larger corporations because each bullet point above requires investment. It is time-consuming and expensive to create and execute a traceable, auditable, and accountable seafood program. In some instances, regional and local grocery store companies may not be able to keep up with the national and international competition in this regard. This certainly does not mean you should avoid purchasing seafood at smaller stores. Many of these smaller retailers do have seafood sourcing standards and are often selling sustainable, local seafood items not found in larger grocery store chains. I encourage you to ask your smaller neighborhood grocery store about its sourcing considerations for seafood before taking your business elsewhere.

Sustainable Seafood Does Exist, if You Know How to Look For It.

If at this point you’re completely overwhelmed with the level of consideration that can go into a simple trip to the fishmonger, I completely understand. The purpose of this guide was not to overwhelm your decision process, but rather to expose the overwhelming amount of time, expertise, and care that is invested into environmental sustainability measurements for seafood. When understood properly, all the hard work environmental sustainability experts have done behind the scenes can be utilized to make a quick decision between this product or that product. I hope this left you with an appreciation for that process and an eagerness to apply it on your next grocery store trip.

The best advice is to seek out as much information as possible when shopping for seafood. If you can determine the product is from the U.S., or you can identify the correct environmental sustainability rating or certification, you’ll be supporting well-managed fisheries or aquaculture farms.

But for most of us, that piece of fish we buy for dinner at the local grocery store chain may not come with all the information we need on the packaging to be certain of its environmental and social sustainability. In these situations, lean on the grocery store to provide you with some guidance. You’ll be pleasantly surprised to find many large U.S. retailers are already into a multi-year seafood sourcing commitment measured regularly by robust assessment practices. These efforts are partly to protect the brand from risk, but they also serve to take the responsibility out of the shopper’s hands and onto experts like FishWise and other similar organizations that partner with retailers. Rewarding grocery store companies that invest in these commitments will signal the importance of expanding these efforts to the entire industry, and will allow you to navigate the seafood section at your local supermarket with confidence.

Written by: Jack Cheney

Produced in partnership with SustainableFisheries-UW.org