In the top northwest corner of Peru sits a small, rural fishing community with an appetite for fishery improvements to meet export demands – a market that sustains their livelihood. This quaint community of fishers supports Peru’s mahi mahi and jumbo squid exports, providing high-value seafood products primarily to North America and Europe. Climbing aboard a mahi mahi fishing vessel docked on the shore of Islilla, FishWise had the opportunity to learn about one cooperative’s journey towards fishery improvements to meet increasing demands for traceability and sustainability assurances. With newly installed satellite beacons, a cell-phone enabled traceability application in hand, the smell of fresh paint, and a willing fisherman to tell us his stories – it was easy to feel the fishing pride held by this small community. This was one stop on a week-long journey to Peru to learn about the country’s traceability efforts and the various fishery solutions being created and implemented by our NGO friends, Future of Fish who are working in close partnership with WWF Peru, which launched the mahi mahi fisheries improvement project in 2013.

FishWise is known as a convener of seafood traceability experts and resources, working diligently with our business partners for over 15 years to implement traceability and counter-illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) practices to support transparent supply chains and sustainable fisheries. But from our desks in sunny Santa Cruz, CA it can be hard to understand how the technological or process improvements we advocate for shake out when companies implement them within their supply chains.

Fortunately, a research project launched in early 2019 has prompted the FishWise traceability team to hit the road, and learn directly from seafood importers, exporters, and suppliers upstream. We have been asking about their experiences adapting to the recent implementation of the Seafood Import Monitoring Program (SIMP), a U.S. government program that requires importers of certain seafood products, such as mahi mahi, to undertake additional reporting and recordkeeping in order to prevent (IUU)-caught and/or misrepresented seafood from entering the U.S. market. Capping off a year of data collection, this project led us to the primary source of the world’s mahi mahi production – Peru!

As small and quaint as the fishing village of Islilla may be, the fish caught by Islilla fishermen travel far and wide, making a global

splash. North of Islilla lies Paita, a neighboring fishing town with offloading capacity and a large port responsible for the majority of Peru’s mahi mahi and jumbo squid exports.

Paita is the northern hub for major fishery exports and houses one of Peru’s three major domestic seafood marketplaces, called ‘terminals’. Though we were mostly interested in the seafood export market and the impact SIMP has had on producer countries sending fish to the U.S., we were excited for the opportunity to explore the domestic market*. Arriving before dawn, it was shocking to see the number of people, products, and processing already taking place and in full swing. In Peru, traceability of domestic catch stops at these marketplaces, because they currently lack national systems and capacity to track a fish’s journey beyond the terminal.

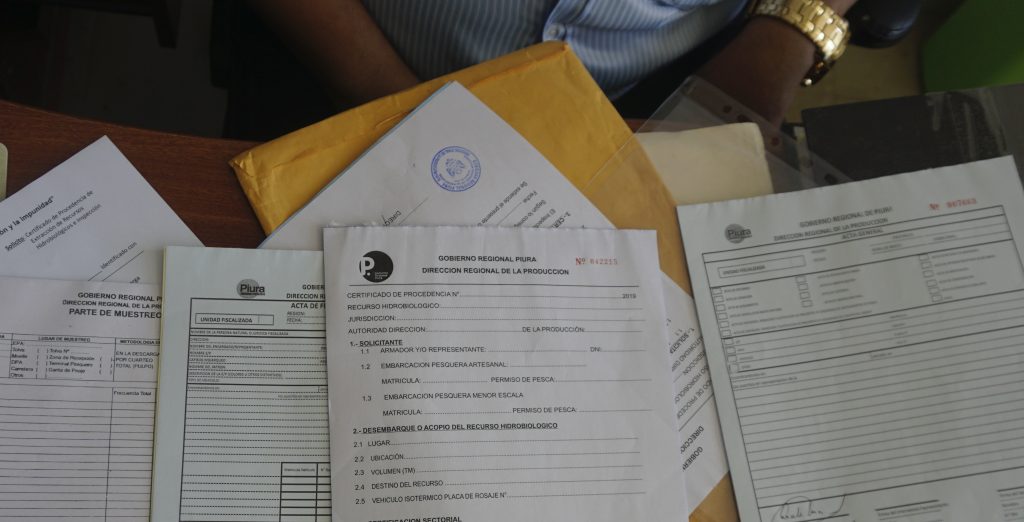

The exported fish, however, continue their traceability journey beyond Paita as they’re iced and loaded onto container ships ready for export to North America or Europe. We had the opportunity to learn about how a producer country is impacted by increasing demands for supply chain transparency, including import requirements such as SIMP meant to deter illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) products from entering their supply chains. More data means more paperwork, which can be especially challenging for an industry that continues to collect and process this paperwork by hand.

Ready for Export

The exported fish, however, continue their traceability journey beyond Paita as they’re iced and loaded onto container ships ready for export to North America or Europe. We had the opportunity to learn about how a producer country is impacted by increasing demands for supply chain transparency, including import requirements such as SIMP meant to deter illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) products from entering their supply chains. More data means more paperwork, which can be especially challenging for an industry that continues to collect and process this paperwork by hand.

At the end of our site visit to Paita, Piura, and Islilla in Northern Peru, the FishWise team ventured south to the bustling metropolis of Lima to attend the inaugural Seafood Lima Expo. We met with Peruvian exporters to learn about their traceability practices and experiences complying with SIMP, and presented on traceability and government reporting efforts taking place in the U.S. during a workshop sponsored by Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP). Seafood Lima gave us one final glimpse into the end of the Peruvian fisheries chain and the beginning of the U.S. supply chain.

One thing we’ve learned from talking to South American exporters, is that in many cases a company’s experience complying with SIMP is dependent on the capabilities of its existing traceability systems and the supporting capacity (or lack thereof) within their national governments. Much of America’s mahi mahi, and other species such as tuna, are caught on artisanal boats without vessel registrations or even space aboard to add the tech systems needed for documenting fishing events. This can pose a challenge for small fishing villages, such as Islilla, that are working to implement traceability practices with little available government support to meet U.S. market demands. Despite these challenges, government and market incentives to improve traceability and sustainable fishing practices can also create opportunities for the fishing sector to work together towards a common goal. It was inspiring to learn about the various NGO and local government efforts taking place to help Peru’s mahi mahi sector meet sustainability requirements (see resources below).

It takes a village to track a fish’s journey across the globe – seafood traceability and sustainability require collaboration across the supply chain, government support, and buy-in from businesses downstream seeking to provide their customers with sustainable, quality seafood with a story tracking its journey from ocean to plate.

We’re grateful for the opportunity to travel to Peru and coordinate with other seafood NGOs to learn about electronic catch documentation and traceability efforts happening on the water, all while gleaning pathways for continued seafood traceability improvements, globally. As we continue our work, engaging with seafood businesses and vendors responsible for feeding the North American market, we will remember these experiences and the different realities of data collection, reporting, and transfer down the supply chain. We will work to incorporate these lessons and perspectives to collaboratively reach our collective goal of healthy oceans, traceable and ethical supply chains, and supporting the well-being of those communities depending on seafood for their livelihoods.

Resources to learn more about NGOs working on mahi mahi sustainability in Peru:

- Future of Fish Contributes to the Sustainable Seafood Movement in Peru: http://futureoffish.org/blog/pesca-consciente-ceviche-por-siempre

- Future of Fish recommendations for implementing traceability in the Peruvian mahi mahi fishery: http://futureoffish.org/resources/research-reports/fishery-development-blueprint-0

- WWF 2017 Report on the Peruvian mahi mahi supply chain: https://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net/downloads/mahi_mahi_value_chain_en.pdf

- Sustainable Fisheries Partnership mahi mahi sustainability report: https://www.sustainablefish.org/Media/Files/T75-Sector-Reports/T75-Mahi-Sector-Report

*50% of Peruvian mahi mahi stays in the domestic market. The other 50% is exported, primarily to the U.S. and European markets. Peru is the leading producer of mahi mahi, supplying over 50% of global market. (Source: Future of Fish