End-to-end, electronic, and interoperable. These are not just words that describe the gold standard for traceability systems. They are also what the seafood industry seeks in technology solutions to tackle the pervasive issues of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing that plagues complex, global supply chains. Traceability technology solutions have noticeably progressed in improving transparency within seafood supply chains, and blockchain is receiving a lot of momentum and recognition for being one of those solutions. Under the right circumstances, blockchain’s framework has the capability to help combat illegality within supply chains, help overcome mistrust of data, and increase the transparency of an often opaque seafood journey. But similar to other traceability solutions, blockchain isn’t a silver bullet. Regardless of what platform, provider, or software is used, there are clear traceability wins and challenges that need to be considered in order to identify which solution is the best choice.

How do you know if blockchain is the right solution for a business? What are some of the limitations to using blockchain? What ‘wins’ can it provide a business? Here, we will explore the considerations discussed in a recent FAO report (Blaha and Katafono, 2020), and highlight case studies and resources to help inform the decision.

What is Blockchain?

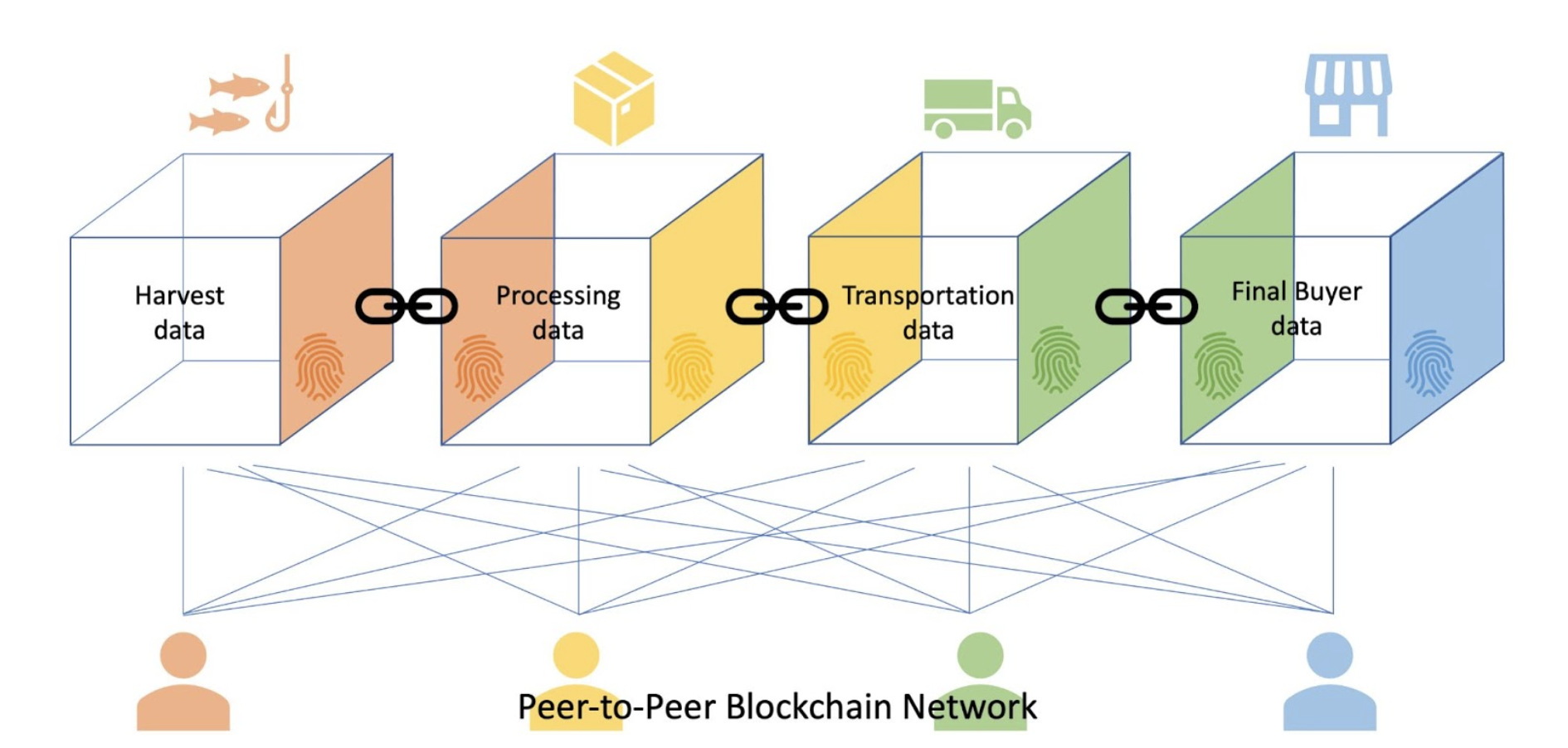

Blockchain is essentially a decentralized and digital list of records that can be securely shared. This list, or “ledger”, expands as it passes through each node, or “participant”, in a supply chain. Being decentralized means that no one participant owns the data or acts as the central database housing all the records, like a bank. Instead, all participants have access to that data. Because all participants are active in a blockchain and able to access data from beginning to end, this creates a peer-to-peer network to help track the movement of digital data in a secure way. This organized movement of data means that information about where, when, and how a fish is caught is passed up the supply chain, and data continues to be added as the product is transformed, shipped, and sold. This transparency among the participants clarifies the often messy middle of seafood supply chains.

Nodes participating in seafood blockchains can be different depending on the purpose and complexities of the supply chains. For instance, the FAO report describes State actors (Flag State, Port State, etc.) as nodes creating a blockchain that tracks when a seafood product changes jurisdictions, which could ultimately help long-term coordination between governments to improve traceability. In this blog, we will think of nodes along the seafood supply chain as critical tracking events (CTEs), such as harvest or transshipment. Each CTE creates a block within the chain that is linked to other blocks by a security mechanism called a cryptographic hash. Each block has two coded hashes (or fingerprints); one hash is unique to each new block created and the second hash matches the previous block. Think of these hashes as creating the link (or chain) between the blocks, ultimately creating the blockchain. For example, a fish processor will add new product data to the ledger, creating a new block. This block will have its own hash as well as the hash linking it to the previous node’s block, such as the harvest event (Figure 1). Once the cryptographic hash is assigned to a new block, it is forever assigned to that specific data. If the data is changed, the hash changes, the chain is broken, which notifies all participants in the network. The hash is a key characteristic of blockchain: promoting unchangeable and immutable record keeping to deter fraudulent activity within the supply chain.

Of the three types of blockchains—public, permissioned (private), and consortium (public/private hybrid)—a combination of a permissioned and consortium blockchain has been shown to have the greatest potential for seafood supply chains. It has lower energy requirements and faster transaction times compared to a public blockchain. One organization manages private blockchains (permissioned) and only approved participants within your supply chain would have access to your blockchain. A consortium blockchain leverages the potential collaboration between companies within the supply chain, and no one organization manages the blockchain. With a permissioned consortium blockchain, business data remains private from the public eye while encouraging coordination among those in the supply chain (fisher, buyer, processor, buyer), which means different companies with different traceability systems all contribute data to describe the product’s journey from bait to plate.

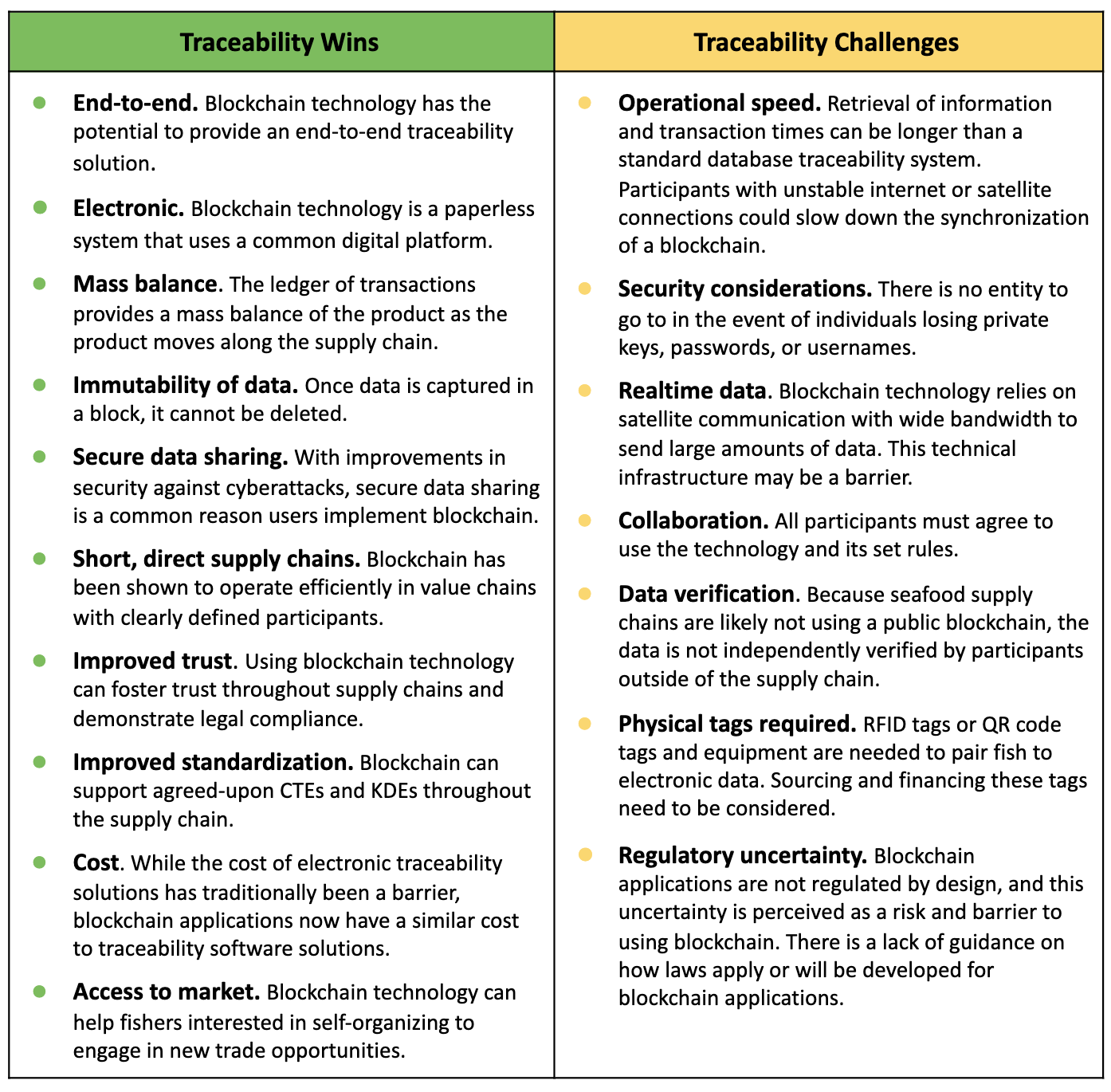

That sounds like the perfect answer to tackling seafood traceability, right? Blockchain has been described as a secure and fully traceable solution, but as seen in the table below, there are also points to consider when adopting blockchain in different seafood supply chains.

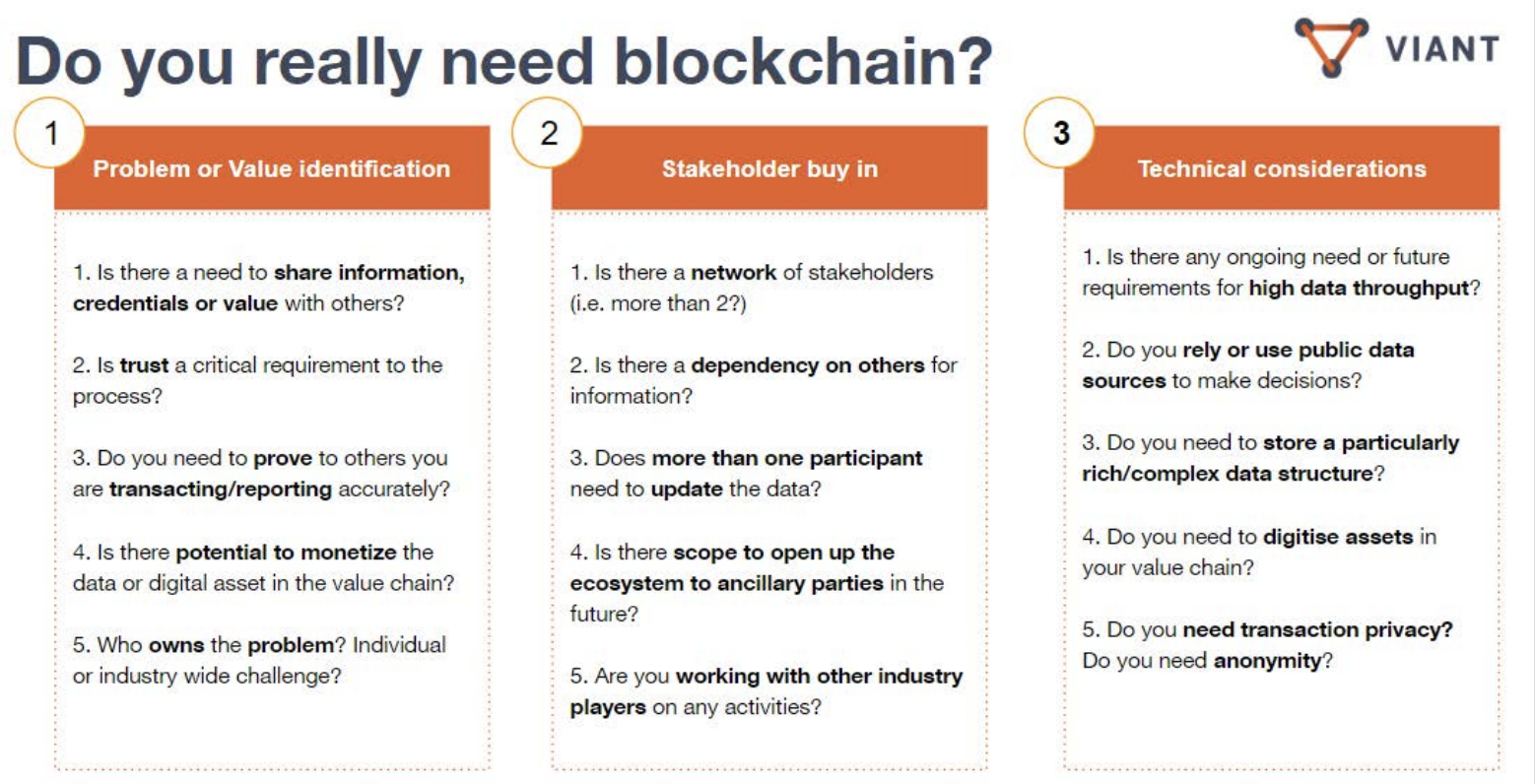

When do traceability wins outweigh the challenges?

Blockchain isn’t ideal for all supply chains, so it’s important to think of the wins versus challenges for a business and understand if one outweighs the other. There are several published decision trees that can be used to help determine whether blockchain should be considered for a business. The FAO report highlighted the Gartner (2019) decision tree adapted from the NIST’s “Blockchain Technology Overview” report (linked below) as a well-designed model. Additionally, some models can help further determine what kind of blockchain makes sense in a specific business case. First, begin by asking, “Do you need blockchain?” If the answer is “yes” to a majority of the questions below, then it may be time to start exploring blockchain options (Figure 2).

Ready to Dive Deeper?

Blockchain technology uses language many of us are not familiar with. Check out a blockchain glossary as you continue to explore the functionality of this technology.

Seafood Blockchain Pilots

- Project Provenance Ltd in Indonesia completed a six-month pilot using blockchain technology for handline, pole, and line-caught tuna.

- OpenSC, co-founded by WWF-Australia and BCG Digital Ventures, is a transparency platform using blockchain technology piloted with Patagonian toothfish.

Blockchain in Action

- Wholechain uses Mastercard’s blockchain for multiple seafood providers including all 14 seafood products in Topco’s Full Circle Market line.

- Fishcoin Project can be used with any seafood product to incentivize the transfer of data.

- Anova Food USA and the Indonesian handline tuna fishery uses blockchain technology to help manage certifications.

- IBM Food Trust blockchain is used by several seafood products as well as the Sustainable Shrimp Partnership to track farmed Ecuadorian shrimp.

- KnowSeafood is an online market that uses blockchain technology with StoryBird application software.