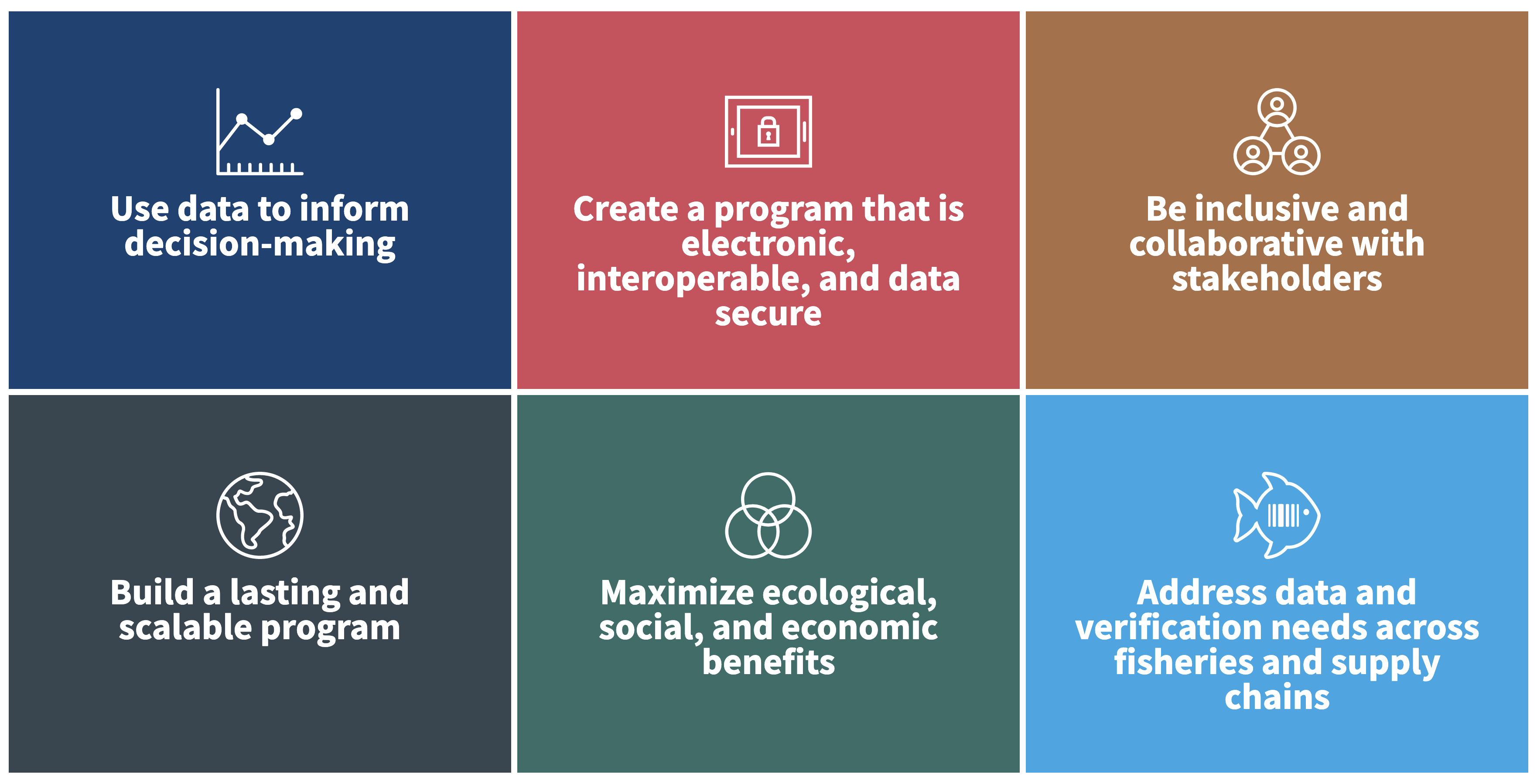

In early 2021, SALT launched the Comprehensive Traceability Principles to help governments in seafood producing countries implement or improve electronic seafood traceability systems that address ecological, social, and economic objectives. One of the six principles is to build a scalable, long lasting system by generating and maintaining support for the eCDT program—politically, financially, and with users—so it can expand beyond the pilot phase.

Generate and maintain support for the eCDT program—politically, financially, and with users—so it can expand beyond the pilot phase.

Learn more here.

To expand the guidance provided in this Principle about scaling up traceability programs, SALT partnered with Institute of Food Technologists’ Global Food Traceability Center, a technology-agnostic, science-based non-profit voice on traceability topics. Here, SALT catches up with Blake Harris and Sara Bratager from IFT’s GFTC about the new guidance they developed.

Q1: Can you tell us about your organization?

Founded in 2013, the GFTC is a technology-agnostic, science-based non-profit voice on traceability topics. After completing a series of traceability-related FDA Food Safety Modernization Act task orders, our vision is a fully traceable food system enabled by interoperable digital solutions accessible to all. We work with key stakeholders to develop traceability standards, best practices, tool development, piloting, and educational programs.

Founded in 2013, the GFTC is a technology-agnostic, science-based non-profit voice on traceability topics. After completing a series of traceability-related FDA Food Safety Modernization Act task orders, our vision is a fully traceable food system enabled by interoperable digital solutions accessible to all. We work with key stakeholders to develop traceability standards, best practices, tool development, piloting, and educational programs.

Q2: Can you summarize your work with SALT and who was involved with this project?

The genesis of this work came from recognizing two factors: First, governments worldwide have recognized the need to facilitate and support traceability initiatives in food supply chains and have begun allocating resources toward pilots and programs. The second is that more guidance was needed to help governments plan their traceability roadmap from creation to implementation and ongoing maintenance. To fill this gap, we created an easy-to-follow checklist of considerations to think through as they develop their traceability plans. While SALT and GFTC have experience working with governments, we also conducted a landscape analysis of published resources, interviewed traceability experts from across the globe, and embedded their insights and links into those resources throughout the document.

The genesis of this work came from recognizing two factors: First, governments worldwide have recognized the need to facilitate and support traceability initiatives in food supply chains and have begun allocating resources toward pilots and programs. The second is that more guidance was needed to help governments plan their traceability roadmap from creation to implementation and ongoing maintenance. To fill this gap, we created an easy-to-follow checklist of considerations to think through as they develop their traceability plans. While SALT and GFTC have experience working with governments, we also conducted a landscape analysis of published resources, interviewed traceability experts from across the globe, and embedded their insights and links into those resources throughout the document.

Q3: What was most surprising about your findings?

What was most surprising about our findings was how difficult it is to scale from a pilot to full implementation. Through our research and interview process, we heard time and again how significant resources and effort were put into planning and executing a pilot that ended once initial funding was exhausted. When you consider the scale and complexity of implementing a national traceability initiative it is clearly difficult to emulate many of the factors in a pilot setting—such as enforcement; the level of effort needed to educate and train all stakeholders; and continuous funding for maintenance and support of the program.

What was most surprising about our findings was how difficult it is to scale from a pilot to full implementation. Through our research and interview process, we heard time and again how significant resources and effort were put into planning and executing a pilot that ended once initial funding was exhausted. When you consider the scale and complexity of implementing a national traceability initiative it is clearly difficult to emulate many of the factors in a pilot setting—such as enforcement; the level of effort needed to educate and train all stakeholders; and continuous funding for maintenance and support of the program.

Q4: Based on your research, why is it important for governments to think about scaling up past a pilot phase from the onset and throughout the development of a seafood traceability program?

Pilots demonstrate technical capability but not necessarily system-wide feasibility. Pilots do not often include administrative elements like fees and fines, inspection and enforcement tasks, or widespread education and outreach, but these are critical components of a national program. Incentivization for industry actors will also become more complex once pilot funding has run out; most actors will not adopt a traceability simply because it’s possible. Governments must plan for system-wide scaling from the outset to build institutional capacity and funding into the program and ensure seafood supply chain actors are adequately incentivized to comply.

Pilots demonstrate technical capability but not necessarily system-wide feasibility. Pilots do not often include administrative elements like fees and fines, inspection and enforcement tasks, or widespread education and outreach, but these are critical components of a national program. Incentivization for industry actors will also become more complex once pilot funding has run out; most actors will not adopt a traceability simply because it’s possible. Governments must plan for system-wide scaling from the outset to build institutional capacity and funding into the program and ensure seafood supply chain actors are adequately incentivized to comply.

Q5: What helpful tips would you suggest to governments when they have challenges with scaling up a traceability program?

Our research revealed some programs were thwarted by a lack of understanding among stakeholders, while others were stalled due to inadequate incentives or insufficient institutional capacity. It’s important governments engage all stakeholders—the data generators and data users—to identify the source of the challenge and make appropriate adjustments. Peer-to-peer collaboration is also helpful. Several interviewees pointed out specific country-level strengths that could be emulated elsewhere and struggles that could be reduced through sharing of best practices and key learning between nations.

Our research revealed some programs were thwarted by a lack of understanding among stakeholders, while others were stalled due to inadequate incentives or insufficient institutional capacity. It’s important governments engage all stakeholders—the data generators and data users—to identify the source of the challenge and make appropriate adjustments. Peer-to-peer collaboration is also helpful. Several interviewees pointed out specific country-level strengths that could be emulated elsewhere and struggles that could be reduced through sharing of best practices and key learning between nations.

Q6: Did you uncover what is commonly missed when building scalable traceability programs that you would highlight for future research?

One thing that stood out through our research was the need for pre-project communication between government agencies and stakeholders. In one case, an interviewee described a situation when a national government decided to develop community landing centers to aid in data collection. The landing centers were furnished with great equipment, but with no stakeholder consultation, they were built too far from the shore in inconvenient locations for fishers. As a result, the centers sit unused. It’s critical governments engage impacted stakeholders to assess needs, expectations, and capabilities to ensure resources are used effectively.

One thing that stood out through our research was the need for pre-project communication between government agencies and stakeholders. In one case, an interviewee described a situation when a national government decided to develop community landing centers to aid in data collection. The landing centers were furnished with great equipment, but with no stakeholder consultation, they were built too far from the shore in inconvenient locations for fishers. As a result, the centers sit unused. It’s critical governments engage impacted stakeholders to assess needs, expectations, and capabilities to ensure resources are used effectively.

Q7: How do you suggest governments use this new tool you’ve created?

This new tool is a great high-level guide for government traceability program considerations, but a lot of work goes into each of the items. Keeping in mind the length of the process of creating regulations, tools, and educational materials; coordinating with all the stakeholders that will be affected by it; and the need to revise as markets and industry norms shift are essential to developing a long-lasting scalable program.

This new tool is a great high-level guide for government traceability program considerations, but a lot of work goes into each of the items. Keeping in mind the length of the process of creating regulations, tools, and educational materials; coordinating with all the stakeholders that will be affected by it; and the need to revise as markets and industry norms shift are essential to developing a long-lasting scalable program.